Carolina Anole

These small lizards have the ability to alternate between two basic colors, unlike chameleons which can modify the appearance of their skin to a multitude of colors to match their environment. Anoles have three layers of pigmented cells in their skin that allows them to change their skin color. The three colors of pigmented cells are brown/black, yellow, and blue. Typically these anoles will be a rich brown in environments that are cool, moist, and/or dark, and also when they are stressed. These are situations when an anole's activity is diminished. They will be brilliant green when they are warm, active, in bright light, and during the excitement and competition of mating season. And of course green comes from the blend of the yellow and blue pigmented cells.

Some individual Carolina Anoles have a light marking along the ridge of their back as in this individual. Carolina Anoles have special toe pads that are a bit like those of geckos that allow them to climb on slick surfaces. They have a prominent ridge that runs from the eye to the nose.

Anoles eat mostly insects and spiders. In winter they avoid the cold in sheltered areas like under tree bark, in thick brush, or inside small outside openings in a house like under this deck where I found these two. Anoles have the features of other lizards, like dry and scaly skin, eyelids, claws, and behind the eye there is an external ear opening.

Male Carolina Anoles have unusual territorial and dominance displays that involve doing a sort of push-up motion that causes their head to bob up and down. Often at the same time they will extend their dewlap, a portion of skin along their neck and throat that is like a brilliant red blade. Below are links to pictures of dewlaps, the two basic Carolina Anole colorations, and a short video of an anole changing colors.

Some of this information on Carolina Anoles came from:

http://animaldiversity.org/site/accounts/information/Anolis_carolinensis.html

and

http://carnivoraforum.com/topic/10155363/1/

Dekay's Brown Snake

On Veteran's Day as I was digging up little volunteer Nandina shrubs, I came across this small snake hiding under leaves next to the house. This Dekay's Brown Snake is common in many habitats across the eastern US including forests and wetlands as well as the lawns and gardens of cities and towns. They are a somewhat secretive snake and often spend their day under leaves, mulch, rocks, and landscaping timbers.

Like all snakes, the Dekay's Brown Snake uses its tongue to gather information about the odors in the air around them as well as from items they may be considering to consume as food. These chemical "scents" attach to the tongue and are processed by the Jacobson's organ which is located in the roof of the snake's mouth. This information is sent to the snake's brain which it interprets as a smell.

The picture below shows the snake curled up on a Formica table top. The two rows of small paired dark spots along its back are a key identifying feature. Dekay's Brown Snakes can be light brown like this one, but can be gray or darker brown as well. This one has cream colored belly, but often the belly is grayish or pinkish.

In this picture you can see the pattern of scales on its belly that identifies it as a non-venomous snake. On the right side of the picture at the snake's vent or cloaca (where the tail starts to turns downward) the scales go from a single scale across the belly to a braided pair of scales. All of North Carolina's non-venomous snakes show this pattern of belly scales while our venomous snakes (except for the very rare Eastern Coral Snake) continue a pattern of single scales past the cloaca nearly to the tip of the tail.

In this close-up picture that I took in a white bowl, you can see a prominent dark mark behind its eye. Another feature that you can see here are the keeled scales along its back and sides. On some of the scales, the keel is highlighted by the camera's flash as a small raised white line in the middle of the scale. These keels make this young 8 inch long snake feel a bit rough when holding it. Dekay's Brown Snakes only grow to about 15 inches long. Though these snakes are a bit wiggly, I have never had one even offer to bite. They eat insects, earthworms, and slugs, etc. Female Dekay's Brown Snakes do not lay eggs, but birth a few to as many as 20 young.

http://wildlifeofct.com/dekays%20brownsnake.html

Southern Two-lined Salamander

Also on Veteran's Day I uncovered this small amphibian while working with a gutter downspout drain. On the wet ground under the corrugated pipe, I saw a little squiggle motion. A quick scoop and I had this beautiful Southern Two-lined Salamander in my hand.

One feature that biologists use to identify salamander species is the number of costal grooves along each side of the amphibian. The Southern Two-lined Salamander has 14 costal grooves**. The salamander's ribs lie just beneath these narrow channels. It appears the function of the grooves is to transport water across this semi-aquatic salamander's thin and fragile skin to keep it moist. You can see several of the vertical crease-like marks in the picture below.

The Southern Two-lined Salamander's basic color is yellow-orange with a broad pair of dark brown to black lines that run from behind the eyes and along the body nearly to the end of its tail. It also has these dark speckles on its sides below these stripes as well as a few sprinkled between them. Its legs are speckled, too.

Salamanders look a little bit like lizards, but are quite different. Salamanders can breathe through their skin which is moist and smooth instead of dry and scaly as in lizards. And salamanders do not have claws or external ear openings like lizards.

The Southern Two-lined Salamander's tail is nearly as long as the rest of its body. Salamanders can detach their tails as a way of escape from a predator or a rival. Within hours the salamander can begin growing a new tail through a process called regeneration.

These sleek little 2.5 to 4 inch salamanders live in and around wet areas like streams, ditches, and seeps (like my gutter downspout drain), and are often found under leaves, rocks, or logs. The adults eat a variety of prey including earthworms, millipedes, roly-polies (pill bugs), flies, beetles, snails, roaches, ants, spiders, bees, grubs, and ticks. Yum!

It is easy to see some of the salamander's internal organs through its very thin, moist, and breathable yellow skin. Its tail is remarkably long.

I took this picture in a white bowl with a small amount of water. Here you can see the four toes on the front feet and the five toes on the hind feet. There are a few salamander species that have four or fewer toes on the hind feet.

adults as including roaches, spiders, ticks, earthworms, isopods, millipedes, beetles, snails, springtails, flies, and hymenopterans.adults as including roaches, spiders, ticks, earthworms, isopods, millipedes, beetles, snails, springtails, flies, and hymenopterans.

diet of adults as including roaches, spiders, ticks, earthworms, isopods, millipedes, beetles, snails, springtails, flies, and hymenopterans.diet of adults as including roaches, spiders, ticks, earthworms, isopods, millipedes, beetles, snails, springtails, flies, and hymenopterans.

adults as including roaches, spiders, ticks, earthworms, isopods, millipedes, beetles, snails, springtails, flies, and hymenopterans.

This is a link to a photo of a pair of Southern Two-lined Salamanders. The males of this species develop a pair of fang-like projections from their nasal area called cirri that are thought to help them locate a mate during breeding season.

I found the link below to a very useful tool for identifying salamanders and other wildlife in a specific area.

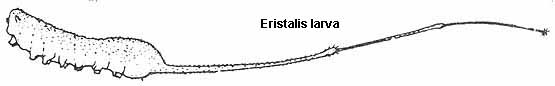

| From: http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus122.html |

Some of this information on salamanders came from:

http://www.herpsofnc.org/herps_of_NC/salamanders/Eurcir/Eur_cir.html

http://www.tnwatchablewildlife.org/

http://www.caudata.org/cc/species/Eurycea/Eurycea_sp.shtml

http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Eurycea_cirrigera/

http://animals.howstuffworks.com/amphibians/salamander-regrow-body-parts1.htm